Time to Talk – How young children acquire language

Young children can acquire more than one language without detriment to learning English and will enjoy greater self-esteem if carers outside the home respect their mother tongue. Anne O’Connor explains why…

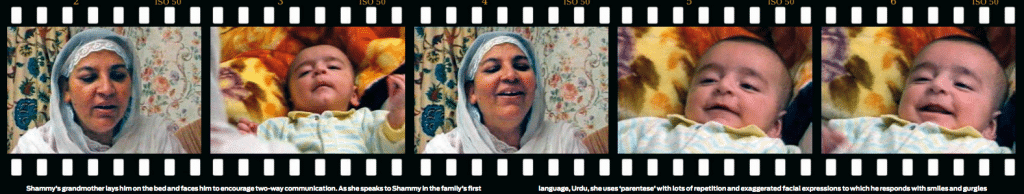

Shammy is in the bedroom with his grandmother. She knows him well and spends lots of time talking and playing with him. She lays him on the bed so that they can have a face-to-face conversation. She speaks Urdu to him, using lots of repetition and facial expression. Shammy will grow up bilingual in Urdu and English.

1 The manner in which people talk to babies is universal. This special way of talking is known as ‘parentese’. Whatever the language spoken, when talking to babies, there is a tendency to use a high-pitched, sing-song voice with enhanced and elongated sounds. Facial expressions are exaggerated too, with wide eyes and big mouth movements. Words and phrases are repeated, often in the form of questions, and the carer responds as if the baby’s babbles and sounds are real conversation. Even quite young children will instinctively do it with babies. So why do we do it?

- Because babies like it! Research has shown that babies are more attracted to the sound of it than they are to regular talk and conversation.

- They are also very interested in faces, and the enhanced facial expressions hold their attention.

- It helps babies learn. Their brains are ‘mapping’ the words and sounds they hear and the frequent repetition builds connections so that comprehension and understanding start to emerge.

- As well as learning about language and conversations, babies are also seeing themselves ‘mirrored’ by the carer. The way that carers wait for a response from the baby – perhaps a smile, a gurgle or excited movements – and then repeat it back to them, helps the baby to learn about themselves, as they see their actions mirrored by the adult.

- It helps parents and carers to bond with their baby. The baby not only enjoys the experience, it also helps them to feel safe and secure and to know that they are loved. At the same time, the joyous responses of the baby make the adult feel good too. The brains of both carer and baby are flooded with ‘feel-good’ chemicals (opiods), which reinforce the pleasure and make them both want to repeat the experience.

2 Being comfortable with two or more languages is the norm for most people in the world.

We tend to forget that even in the UK there is a historical tradition of English being spoken alongside other languages such as Welsh, Cornish, Manx and Scottish/ Irish Gaelic. And yet, there persists this misguided belief that speaking another language in the home will have a detrimental effect on a child’s ability to learn English. Research not only shows us that this is not true, but indicates that for children who live their lives bilingually, ‘using both languages aids cognitive development and strengthens their identities as learners’ (Goldsmith research, see References).

Whereas young babies respond to and are attracted to ‘parentese’ in any language, child development studies suggest that by nine months, babies have an understanding of the general characteristics of the languages relevant to them and become less responsive to others.

This is probably because the brain starts ‘pruning’ connections that are no longer required (which helps explain why some of us find later language learning so hard!). A baby being brought up in the UK will be exposed to English regardless of whether it is spoken in the home, but needs also to frequently hear their family language and have it spoken to them.

Download full article below Time to Talk

Article written by Anne O’Connor and published in Nursery World © www.nurseryworld.co.uk