A sense of security helps young children cope with minor stresses & anxiety

Young children can cope with minor stresses and anxieties if they feel secure in their relationship with their carer, as Anne O’Connor explains…

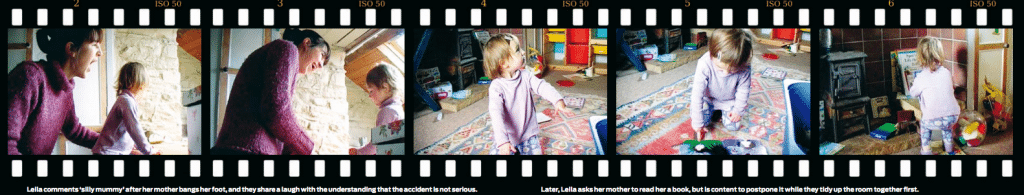

Leila and mum are together at home. Mum bangs her foot and Leila responds by calling her a ‘silly mummy’ when she sees that mum is OK. They both laugh together about it.

When a young child is securely attached, they can begin to appreciate that their caregivers can have feelings and needs of their own. As Leila is quickly reassured that mum is OK, she is able to respond in an affectionate, jokey way that is appropriate to the situation and which she will have experienced herself in other contexts.

Then Leila wants mum to read her a book. But mum insists that they tidy up first. Leila is able to accept this and begins to tidy up. She is secure enough to be able to accept that sometimes what she wants has to be negotiated and deferred for a while. There is evidence in this sequence of the real partnership that can begin to develop when secure attachment is established.

See attachment theory in practice

Find out more about attachment theory with The Early Years Clip Library. Watch documentary videos showing the attachment process from birth to three years old. Start your 30 free trial today. Or keep reading and find out more...

Attachment training videos1 Leila is a good example of a child who has a secure attachment to her caregiver.

This happens when a child has a safe, affectionate and predictable emotional bond with their attachment figures. The special features of these relationships, whether primary or secondary, are sensitivity, affection and responsiveness.

Secure attachments provide a safe base for a child, reducing fearfulness and stress while building confidence and self-esteem. Leila has learned, through countless positive experiences, that her mother can be relied upon to meet her needs.

Very importantly, this secure feeling has also helped her to develop effective ‘stress regulation’ which means she doesn’t need to overreact to small stresses, such as not getting what she wants and having to tidy up first.

When a child doesn’t have enough of these positive experiences, they will have been overloaded with stress chemicals and the alarm systems in their lower brain will be overactive. This means they are likely to overreact to minor stressors and not be able to regulate easily, in the way Leila does.

2 A less secure child is a more fearful child, although the fear may be expressed in different ways.

Some children may find it hard to empathise and recognise that their carers have feelings and can be hurt. Because they are fearful that their own needs may not be met, they shut down their reactions and avoid having to connect with the pain of others.

If this had been the case for Leila, she would probably not have appeared to register that her mum had hurt her foot. Her brain will have registered it, however, and will be flooding with stress chemicals as she struggles to contain her fears for herself – and possibly for her mother.

On the other hand, for some children, insecure attachments may make them hypersensitive and full of fear when they see others experience pain. This is particularly true if it happens to be someone they depend on for their own well-being, whether or not they can be relied on. If Leila’s mum is hurt, this might pose a threat to her own survival.

For Leila this might have meant that she became upset when her mother hurt herself, and possibly angry. She certainly wouldn’t have been able to respond affectionately. The root of all this anxiety is ultimately the fear for our own survival.

Stress response systems in the brain of a child with healthy attachments work effectively to stop them having to react to minor stresses, keeping them calm and relaxed. They don’t need to ‘sweat the small stuff’, because they are confident their survival is not at risk.

The brain of an insecurely attached child has repeatedly been flooded with cortisol (a stress chemical), so their threshold for coping with stress is lower. Children with disordered attachment might even become so stressed that they seek to mock or increase the pain of the other person, as a way of dealing with their own intense feelings. This is often misunderstood as heartlessness or a need to ‘kick someone when they are down’.

Download full article below A Sense of Security

Article written by Anne O’Connor and published in Nursery World © www.nurseryworld.co.uk